Gears magazine, May 1997, "Ask The Experts" column, brought up an interesting issue with TV cable setup, position and operation, covering the types of problems that arise from an improper custom TV cable and lever installation.

To continue with that theme, in this issue covering high performance, I thought I’d address one of the most common requests we get here on the ATRA HelpLine: a compilation of tips and recommendations for adjusting shift timing and feel, by changing springs in valve bodies, governors and other hydraulic control components.

Many high performance engine modifications may require different shift schedules, as a result of the modifications performed. For example, after the engine modifications, engine speed may now easily exceed 8000 rpm; the shift times need to be changed to make use of this extended rpm range. These changes may also require shift feel modifications to compensate for the increased power output.

As with many technical discussions, differing opinions or disagreements arise, regarding the approach used to address a problem. Keep in mind that this article will be highlighting concepts, suggestions and ideas that have worked in the past. They are by no means ironclad rules, or "the only way."

In fact, the only ironclad rule that applies here is that if something works for you, and works properly, then keep doing it. Don’t mess with success. However, there may be times when a slight change in shift time or feel would do some good, or might fix a nagging little problem, but you’re not sure how to proceed. That’s where we come in.

Submitted for your approval is a collection of the processes and ideas that go through our minds when certain hydraulic calibration, modification or troubleshooting questions arise on the HelpLine.

Square One

Probably the most easily-avoided, time-consuming and common mistake made during the adjustment or diagnosis of a TV-controlled transmission is to move the TV cable adjustment around in an attempt to correct a shift timing or shift feel problem. This can also be one of the quickest ways to burn up your work.

Set the TV cable position once, according to the Gears article mentioned earlier, then leave it alone, regardless of how the unit works. If the TV plunger is bottomed into the valve body at WOT, and there is a little TV plunger-to-paddle air gap at an idle, cable position is within one or two clicks of where it needs to be. Changing this position won’t correct a problem: It just creates another problem on top of the first one.

Changing TV cable position doesn’t correct a governor, shift valve or clutch problem, but it can hide one … for a little while. Cranking in lots of extra TV might hide an early shift problem for a little while by opening kickdown circuits at half throttle. But this doesn’t fix the TV or line rise problem actually causing the early shifts: It just makes you think you did, until the fried, shriveled up, stinky unit comes back through your door, after the cable readjusts itself, the way it was designed to.

Before attempting to correct any problems using these modifications, always verify the proper operation of the throttle valve and line pressure rise systems with a pressure gauge. Unfortunately, counting how many times the little plastic dog in the back window nods his head after a shift just isn’t an accurate test of the hydraulic systems (no SAE calibration standards have been written for plastic dog neck springs yet…).

Line rise must respond to throttle correctly for these modifications to work. A TV limit valve in a 4T60 at full throttle in D4 won’t send the proper 90 psi to the throttle valve, if mainline pressure never exceeds 60 psi, due to a PR boost valve or modulator problem. Likewise, don’t expect a 4L60 line bias valve to allow 60 psi through to the PR boost valve if the TV limit valve is stuck open, leaking anything over 20 psi right back into the pan.

Having nagged enough about that, let’s move along to—

Adjusting Shift Speeds and Shift Feel

The governor is usually much easier to work with than the valve body. Consider going here first if you need changes in either of these two areas:

1. All upshifts can be made earlier, and kickdown can be made less sensitive by increasing governor pressure for any given speed.

2. All upshifts can be made later and kickdown can be made more sensitive, or easier to get, by decreasing governor pressure for any given speed.

Keep in mind that all upshift and kickdown speeds will be altered when changing governor pressure. To increase or decrease governor pressure, first determine whether you are working on a weight type or a valve type governor, to determine what changes to perform, to get the shifts where you want them.

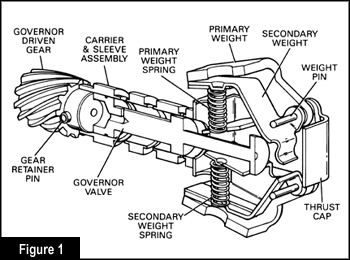

Weight Type Governors

|

|

To change governor pressure on the 350/4L60/ATX-style governor, you can change either one, or both, of the springs in the governor (it doesn’t matter which one), or the thickness or size of the inner weights. The 200/4T60/AXOD weight-type governors have one large and one small weight. To change governor pressure on this type, change the spring on the small weight only, or change the thickness or size of the small weight only. On both style governors, stiffer springs or larger (heavier) weights will increase governor pressure at any given speed. Weaker springs or smaller (lighter) weights will decrease governor pressure at any given speed. Valve-Type Governors Valve-type governors are the C6, Torqueflite or FMX-style governor. This style allows centrifugal force to act directly on the valve that controls, or regulates, governor pressure. On valve type governors that have two valves, governor pressure is changed by modifying the spring on the smaller, or secondary valve only. The secondary valve and valve spring will be positioned in the governor body or housing in one of several ways, depending on design: |

1. On governors where a secondary spring holds the secondary valve outward, away from output shaft or center of governor (typical C4/C6 style, figure 3): Increasing spring tension increases governor pressure at any given speed, causing earlier shifts and less-sensitive kickdown shifts. The unit will shift out of kickdown at lower speeds.

2. On governors where a secondary spring holds the secondary valve inward, toward the output shaft or center of governor, increasing spring tension reduces governor pressure at any given speed, causing later shifts and easier, more sensitive kickdown. Units will achieve higher speeds in kickdown before shifting to higher gears.

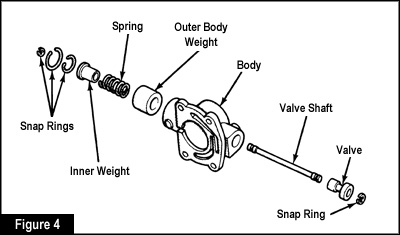

3. On governors where a secondary spring in a different part of the governor acts on a secondary valve through a rod or shaft, such as in a Torqueflite governor (figure 4): Although this configuration seems strange, as if there is no spring to operate the smaller valve, this is the reason for the little rod going through the governor. The spring inside the large weight operates the small valve, and pulls the valve inward, toward the output shaft, just like governor style two.

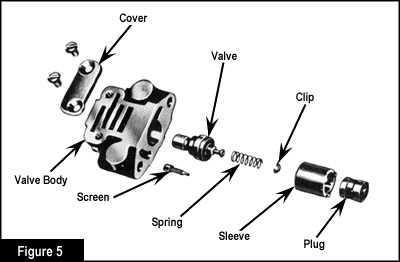

4. On governors where the spring is attached directly to the valve, such as the FMX/AOD-style governor (figure 5): Although quite different in appearance, and having only one valve in the governor assembly, this governor adjustment method is similar to governor style one.

The governor system changes described here won’t change shift feel, at least not directly, although shift feel may become either softer or firmer as a result of the change in shift times, caused by differences in vehicle load vs. engine torque.

Other Shift Time Changes

Note: There are also differences in shift valve land sizes between different vehicle models and calibrations that determine shift speed, along with matching shift valve sleeves. When changing valve bodies, always compare a few shift valve land diameters between the old and new valve body, to make sure there are no major differences between them. Due to the difficult-to-predict nature of changing these valve diameters, any modifications to shift time or feel should be performed using the other methods described in this article.

TV System Changes

In most cases, the TV system affects both shift time and shift feel. Any changes to the TV system, at or before the throttle valve itself, will affect both shift time and feel.

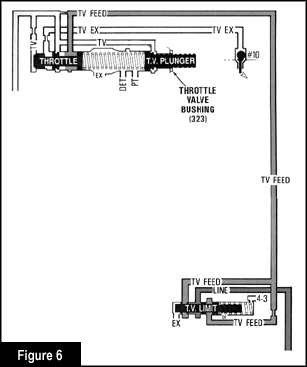

You can increase the TV system performance across the board by modifying the oil pressure that feeds the TV system. The valves that control the throttle valve’s feed pressure are usually called TV Limit, or Shift TV valves (figure 6).

Typically, replacing the spring on this valve with a slightly heavier spring will provide later medium and heavy throttle shift times, easier kickdown that holds to higher speeds, and an increase in line pressure rise above light to medium throttle. This usually provides a perkier shift pattern. But be careful: A little goes a long way.

In some cases it may be necessary to change only the shift speed or shift feel, but not both. Many TV control systems have TV pressure modifying valves, downstream from the throttle valve itself, designed to affect just one or the other. The most common examples of these type valves are:

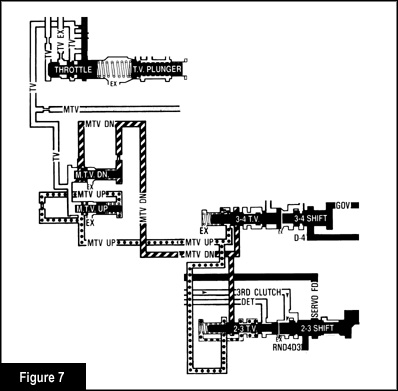

1. Modulated TV (MTV) Upshift and Downshift valves found on many later model GM front and rear wheel drive units (figure 7). These valves are part of shift speed control.

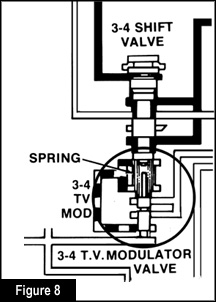

2. Throttle Modulator valves found on various Ford units. These control individual shift valves, which are also used to help control shift speed (figure 8).

3. Line Bias valves, used on GM units, control line pressure rise, or shift feel. Cutback valves also affect line pressure rise by dropping the TV pressure to the pressure regulator valve a small amount, at around twenty to thirty miles per hour, to prolong seal life and reduce engine load.

In most cases, only TV modifying valves that sit after the throttle valve can change shift time without causing shift feel changes. These are regulating valves that receive TV pressure from the throttle valve, then "step it down" a certain amount.

In the examples shown in figures seven and eight, zero-to-very light TV pressure is completely blocked by the modifier valves. As TV pressure rises higher, it forces the valve to move, allowing some TV pressure past the valve. The amount of oil pressure blocked, or stepped down, by these valves is one of the variable characteristics of the valve, and one of the areas you can adjust for a certain effect. Throughout the entire throttle pressure range, the modified pressure will always be lower than TV pressure by that same "stepped down" amount.

Here’s a theoretical example: When TV pressure is below 30 psi, none of it gets past a certain MTV Upshift valve to reach any shift valve. Above 30 psi TV pressure, the MTV Upshift valve begins to open, allowing some TV flow to reach the shift valve. At this TV pressure and above, our example MTV Upshift valve will reduce the TV pressure allowed past it by 30 psi. At 45 psi TV, there will be 15 psi modified pressure going to the shift valves. 60 psi TV will be reduced to 30 psi at the shift valves. 75 psi TV will be reduced to 45 psi, and so on.

These valves allow transmission shift times to be calibrated over a wider range than would be allowed by the TV system alone. Also, the needs of the pressure rise system can be synchronized more closely with the needs of the shift timing system. The amount that a modifier valve drops the incoming TV pressure can be anywhere within a wide range, and these "pressure dropping" tasks can be shared between more than one valve, such as on many GM units with an MTV Upshift and an MTV Downshift valve.

How do these valves affect shift time? The MTV Upshift valve has a rather weak spring opposing incoming TV pressure. So this valve doesn’t drop TV pressure very much. Most of the TV pressure is allowed past this valve, and is responsible for opposing governor pressure and spring tension to delay upshifts while accelerating.

The MTV Downshift valve blocks most of the TV pressure sent to it, allowing oil pressure through to the shift valves only at heavy or full throttle. This pressure applies to different lands on the shift valves than those used by MTV Upshift oil; this is because MTV Downshift oil needs to have a different effect on the shift valves, at different times than MTV Upshift oil. This pressure is calibrated to force the shift valves to downshift below a certain governor pressure, or vehicle speed.

With these principles in mind, here’s how to adjust the effect of these valves. If the spring on this type of valve is made weaker, it will block less incoming oil pressure, allowing a greater percentage of incoming oil through the modifier valve. On MTV Upshift valves, this will result in later upshifts throughout all throttle settings, most noticeably at light and medium throttle. A weaker MTV Downshift valve spring will not affect upshift speeds, because this pressure doesn’t act on an effective area of the shift valves until the valves are in the upshifted position.

Conversely, stiffer springs on these valves will increase the blocking effect of these valves, resulting in earlier upshifts, less sensitive kickdown, or upshifting out of full throttle kickdown at lower speeds.

Modifying Shift Feel

If you don’t want to change shift speed much at all, but you don’t mind changing most or all of the shift feel characteristics, look for a line bias valve or pressure modifier valve between the throttle valve and the pressure regulator valve. This is one of the places where hydraulic flow charts come in real handy. For firmer shifts, use a stiffer spring on this valve. A weaker spring results in softer shifts.

A very effective area that will adjust shift feel of most, if not all shifts, is at the pressure regulator boost valve, or valves. These valves, and their matching sleeves, control both line pressure rise and reverse boost pressure, and depending on the model unit, can come in several different diameters, sizes and shapes.

This allows you to change the force of the boost valve acting on the pressure regulator valve, resulting in higher line pressures, without having to modify the hydraulic pressure going to the boost valves. The larger diameter of the valve, or the greater the difference in area between the two boost valve lands, the higher line pressure will rise for a given amount of TV pressure. Of course, smaller diameters will result in lower pressures for a given amount of TV pressure.

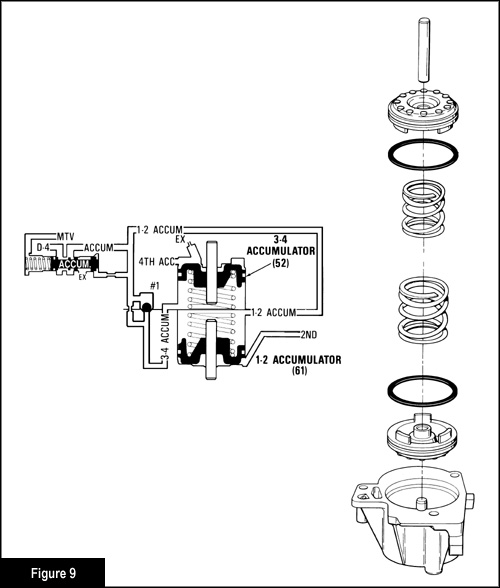

One of the easiest areas to modify to change shift feel is the accumulator piston spring or springs (figure 9). To make a shift firmer, slow down the travel speed of the accumulator piston. To soften a shift, speed up the accumulator piston.

First determine whether the spring on the accumulator is compressing or relaxing during a shift you want to modify. Consult a flow chart for the unit you’re working on. If the spring is compressing during the shift, a firmer spring will make a firmer shift and a weaker spring makes softer shift. If the spring is relaxing, the opposite is true.

One other system that can affect the feel of more than one shift is the accumulator pressure system, not to be confused with the accumulator pistons themselves. The accumulator pressure system has a modifier valve, called an accumulator valve (figure 9).

Most accumulator valve systems use TV pressure to determine engine load. These valves control the oil pressure behind the accumulator pistons, which opposes clutch or servo apply oil pushing on the other side of the accumulator piston. As a result, this accumulator pressure follows throttle pressure, being low at lighter throttle positions, and higher at heavier throttles. This allows the accumulator piston to move easier at light throttle, while making it harder to move at heavier throttle.

The easier the accumulator piston strokes, the more clutch or band apply oil it allows down its bore. Since the accumulator is consuming a lot of apply oil at light throttle, there is less oil actually getting to the applying clutch or band, resulting in a softer shift. The stiffer, or slower the piston stroke speed is at heavier throttle, the more line pressure that reaches the clutch or servo, rather than pushing the accumulator piston down its bore.

These are the first areas to turn to when modifying shift time or feel. Give them a try next time you’d like to adjust these shift characteristics…they should give you the changes you’re looking for.

![]()